When we think of art, some of us picture great works hanging on the walls of an art museum while others might describe graffiti on the side of a train. Some think of the tortured artist in his paint-splattered workshop, wracked with frustration and self-doubt; others envision the riveting performer at the peak of success. For the artists themselves, the experience of creating is often closer to a meditation. That mediation is uniquely human and seemingly fundamental as it spans across every culture. The artists’ process, while appearing different for everyone, always consists of a feedback loop with oneself.

Art is an internal dialogue

For all of us, art was a first language that many of us stopped. Senior Hailey Horak pursued it single-mindedly. Filling hundreds of sketchbooks, Horak finds the act of creating and the act of reflecting to be the same.

“If it’s a feeling or if it’s an [original character] that I made in my head, I have to get [it] out,” Horak explains, “I can clearly see my feelings or thoughts and it helps me get it out and process it.”

While many abandoned childhood drawing in pursuit of spoken word, Horak evolved art into a language of her own — one in which she can frame her emotions in a safe and constructive way.

It is said of theater that all that is required is spectacle and audience; the same can be said for the other arts. The audience is a necessary component as they bring their own emotional content to the piece. That said, art need not be shared or displayed – the artist can be the audience to their own work. For much of art, the artist is the only witness. As an example, imagine a stack of sketchbooks for any practicing artist that linger, forgotten, in a corner of their studio – pages filled with exercises and ideas that no one else will see. Art is, in its essence, a relationship between the artist and the audience — and the artist and themselves.

Art is patient

In every relationship, you need space. A healthy internal dialogue between the art and their work is fueled by a breadth of experience, with which to share.

Senior Phoebe Ensell claims, “You need breaks from things because it can burn you out or just get tiring. I think it’s important so you can regenerate your creativity and experience art on deeper levels.”

New experiences have the ability to expand our personal horizons and change our perspectives on the world. These new ideas can be transformative to an artists’ work, but in order for them to be transformative they must first exist. They must be sought – and this takes time.

Ensell continues, “I will always go back to art and find it again, even if it isn’t in the same way.”

Art may be temporarily abandoned for a variety of reasons, the least of which is to keep the conversation fresh when the artist returns. Regardless of the reason for taking a break from art, one should not be concerned with losing art skills. Once acquired, they cannot be lost – only misplaced. Art is patient; it does not mind waiting weeks, months, even years, to be picked back up again.

Art is for anyone

Whether one is just beginning their exploration of art or is contemplating starting, the efforts can be as relaxing or intense as you chose to make them.

Junior Jenna D’Angelo says art should not intimidate beginners, “…I would tell them to paint anything and everything they want. Art is 110% subjective and something I love, someone else may not. Honestly, I’ve always been self-critical about my art but either way, if you don’t like what you make, you’re still learning from that and can create something new instead. Any failure teaches you a lot and you can always try again with art.”

Part of what makes art liberating is learning to look at mistakes objectively: they become opportunities. There is no shame in being a beginner at anything, especially art. There is perhaps no better exercise that teaches that lesson.

The word “amateur” has an overwhelmingly negative connotation – but it comes from the Latin amare (“to love”) and the Italian amatore (“lover”), to the word “amateur”, which emerged in late 18th century France. Being an “amateur” artist is hardly shameful – one does art for the love of it. Art is for anyone who has stopped and admired a piece and wished it their own.

Art is also for yourself

Even professionals can take time to make art for themselves.

Senior Bella Rink is a special effects makeup artist for a haunted house. She also has numerous artistic hobbies, which she enjoys on her own. Rink explains, “I have felt pressure to do art for others. Working at a haunted house as a makeup artist can be stressful at times. You are literally transforming the actors into a new person or character and if they don’t feel confident in their makeup and costume, it could throw off their acting for the whole night.”

Rink continues, “Although I enjoy doing art for others, I’d rather do it for myself. I’m a perfectionist and like tailoring it to my preferences – when you’re doing art for someone else, their vision most likely won’t match yours, which can put pressure on artists.”

While art can be made into a profitable vocation for some, it is okay to do art for one’s own enjoyment or for the sake of creating. Using your hobbies for yourself is always valid.

Art is therapeutic

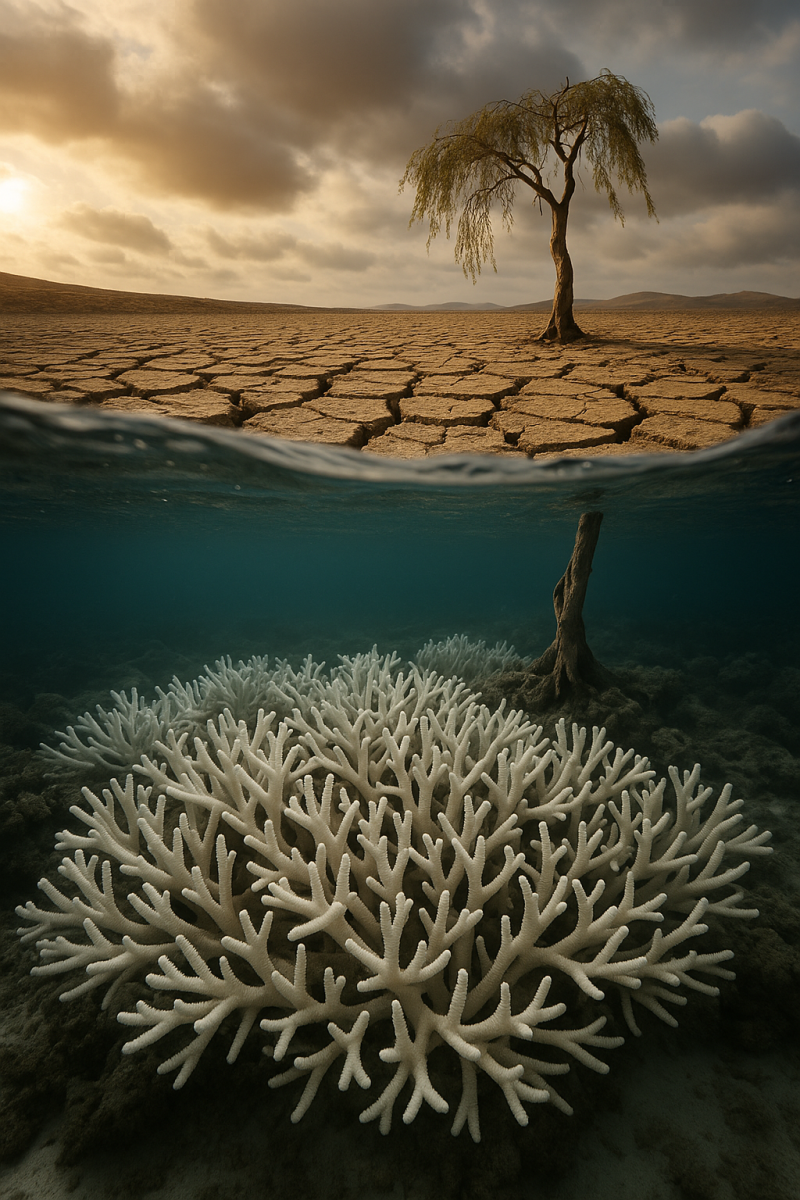

Art can take multiple, unexpected forms. Preconceived prejudices of its format serve no one, as art as in every form just as healing and beneficial as the next.

Senior Isabella Pander believes, “Art helps with mental health tremendously. When I feel down I like to do my makeup to feel better about myself – not just because I like how it looks, but also the fact that I can do whatever style I want to express how I’m feeling. I can change it up some days and I think that’s truly beautiful…art is all about experience and the idea to put your internal feelings onto a canvas to express those experiences.”

Pander adds, “Whether you choose to paint on a canvas or write down lyrics to a song you want to make – it’s all about feeling and creating based on that. And for my canvas, it just so happens to be my face.”

Art and mental health are associated, often in ways that are harmful. The stereotype of the tortured artist, for example, often deters artists from seeking help as it claims that suffering is a prerequisite for creating. Vincent Van Gogh is frequently identified as such an artist, when in reality, his mental health stunted his creativity and his famous paintings were thus created in recovery. Almond Blossom, for example, was painted for Van Gogh’s newborn nephew, as almond blossoms represented hope. Suffering is not a prerequisite for art, instead, quite the contrary is true: art can be a safe means to heal or cope. Art is therapeutic.

…and art is what makes us human

While art is often described as a skill or a discipline, it is first a behavior.

Senior Kyleigh Berisko extrapolates, “By putting a price on hobbies, or trying to determine the ‘value’ of them, artists and writers are deterred from creating. It enforces the idea that, ‘if it is not good, it is worthless, and therefore, it is not worth time and effort.’ This mindset is extremely harmful to all artists, especially young ones.”

When art is made into a skill, the point of creating becomes “to get good at it”, and not simply creating because it is a human behavior.

Berisko continues, “Frost and Wilde, da Vinci and Kahlo, there are so many examples, and they all had to start somewhere”.

Creating – art, music, stories – is a baseline human activity and thus, there exists no naturally imposed hierarchy – any is a construct of our culture and society, and has little to do with the act itself. Many young artists say they “can’t” draw, which is particularly saddening because we have applied such a hierarchy to art. This causes budding artists to feel ashamed for not living up to superficial standards. Creating is the same for the “master artist” and the “beginner artist;” it serves the same fundamental and essential purpose: the internal dialogue.

Berisko reflects, “Artists, musicians, poets, and writers: it’s okay to enjoy your hobby. Have fun, and love what you do.”